If you’ve been to New York City, there’s a good chance you’ve been to Central Park. It is one of the many joys of living and running here. In fact, it is one of the most popular choices by clients for a tour. It is a bucket list item for any runner, both local or visitor to the city, and it is something we could never get tired of running through and sharing with others. We get the opportunity to tell the story of the park and provide information that always surprises our clients.

For instance, did you know that the inspiration for Central Park was a cemetery? In the mid 1800’s, residents of the city and in particular Brooklyn would travel to Greenwood Cemetery and stroll through the open land for fresh air amongst those buried there. Also, at least five waterfalls exist in Central Park, all of them running with the city’s tap water. Coming straight from the Catskills to the Jacqueline Onassis Reservoir, the clean water is technically suitable for drinking, although you’d probably get some strange looks.

But there’s a part of the story of the park we never get to see and often do not hear about. It’s a piece of hidden history that goes back to the 1820s, when this land was largely the open countryside of New York. The expanse became home to about 1,600 people — many of whom were escaping the crowded and increasingly dangerous conditions of lower Manhattan. A place called Seneca Village.

Before we get into the story, let’s go back a little further. What many people do not realize is that New York City in the late 1700’s was second only to Charleston, SC in numbers of slaves, and that it would not be abolished until 1827, at least on paper.

This is what made Seneca Village such an important time in NYC history. It was an opportunity that African Americas had never had before, that would draw a connection between the aspirations that Seneca Village represented for the black families who invested in property there and the racial torment they often faced in crowded upstart Lower Manhattan.

In 1825, landowners in the area, John and Elizabeth Whitehead, subdivided their land and sold it as 200 lots. Andrew Williams, a 25-year-old African-American shoeshiner, bought the first three lots for $125. Epiphany Davis, a store clerk, bought 12 lots for $578, and the AME Zion Church purchased another six lots. From there a community was born. From 1825 to 1832, the Whiteheads sold about half of their land parcels to other African-Americans. By the early 1830s, there were approximately 10 homes in the Village. And when Irish and German immigrants moved in, it became a rare example of racial harmony in an integrated neighborhood during this period.

There is some evidence that residents had gardens and raised livestock in Seneca Village, and the nearby Hudson River was a likely source of fishing for the community. A nearby spring, known as Tanner’s Spring, provided a water source. By the mid-1850s, Seneca Village comprised 50 homes and three churches, as well as burial grounds, and a school for African-American students. Even though slavery was abolished years prior, the African American community were continually discriminated against and often times their lives were threatened. Seneca Village gave them a real sense of community and safe place to be.

All that changed on July 21, 1853. Through eminent domain, New York City took control of the land to create what would become the first major landscaped park in the US, Central Park. The city set aside 775 acres of land in Manhattan—from 59th to 106th Streets, between Fifth and Eighth Avenues. This was a common practice in the 19th century, and all of the residents were displaced throughout the area. Although landowners were compensated, many argued that their land was undervalued. Ultimately, all residents had to leave by the end of 1857. Their currently is no definitive research about where they were relocated. It is believed that some may have gone to other African-American communities in the region, such as Sandy Ground in Staten Island and Skunk Hollow in New Jersey.

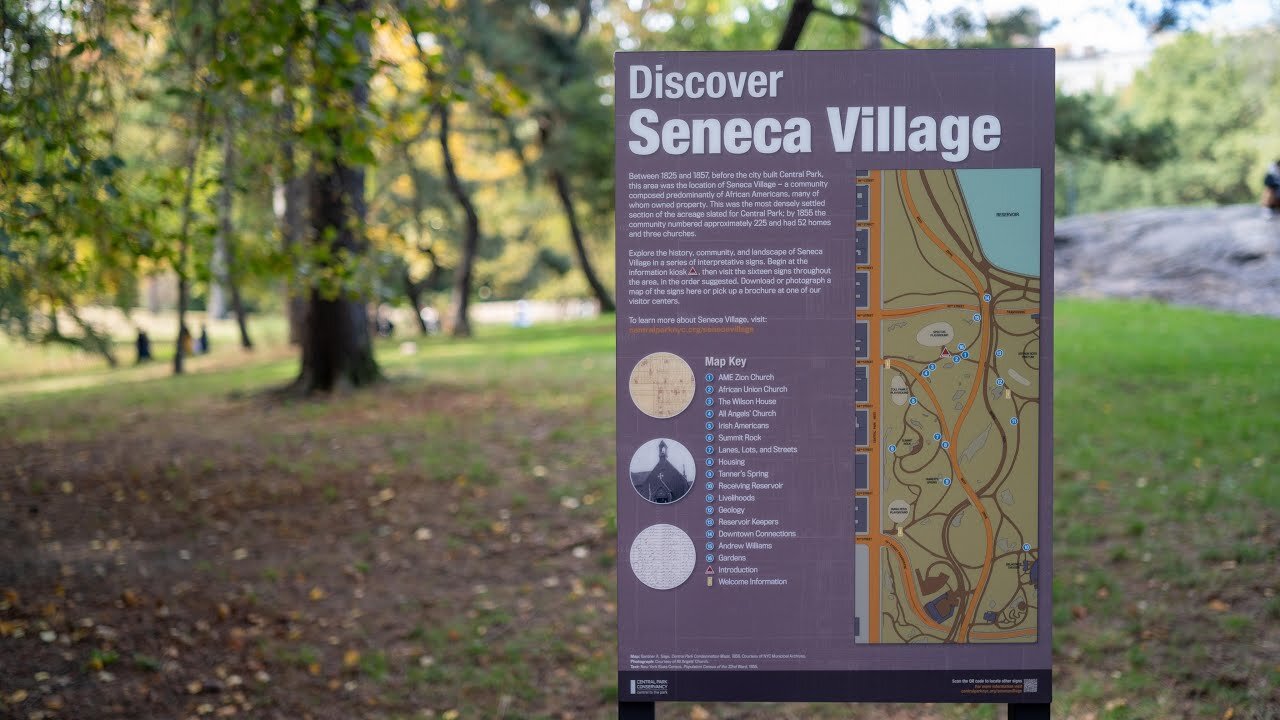

The Central Park Conservancy tells the story of the history of Seneca Village on their website and now along the west side of the park between 82nd and 88th Streets, there are informative signs that describe the people, places and events that took place here during this time period. Remnants of a few structures that were built then remain, along with Summit Rock, the highest natural elevation in the park, standing as a symbol of the past helping preserve a once thriving, diverse community.

It is not uncommon for an ever changing landscape to occur throughout the city. Things come and go all the the time. However if we do not share the history we will never know the truth and be influenced by the amazing people and things they accomplished during this time. We feel we can learn a lot from the people of Seneca Village. There is a very informative New York Times article, The Death Black Utopia, by Brent Staples that we encourage you to read. It describes in more detail the formation of Seneca Village, how the people who lived there created a thriving community and how it unfairly came to an end.

The next time you are running down West Drive in the 80’s stop and check out all of the information or explore with us on our Lower Central Park Tour to learn more about Seneca Village.